Flying by bush plane to Fort Portal, the landscape as we flew south grew greener, more tropical and more mountainous, and we landed on a grass strip on a hilltop where a crowd of locals had gathered to greet us.

This is banana country here; you can see guys on bicycles balancing heavy loads of banana bunches on their way to the markets. Bananas are a staple crop in Uganda — they mash and cook the green ones to make matooke, the principal starch dish that replaces rice or potatoes elsewhere. They also make beer, wine and gin from bananas but sadly we didn’t have the opportunity to sample any during our stay.

We drove for several hours through this hilly part of the country along badly rutted and muddy roads to get to the Ndali Lodge in the crater lakes area. Ndali Lodge — a charming, old-style place with running water but no electricity — sits high on a skinny ridge between a crater lake on one side and a cultivated valley on the other. Upon arrival in pouring rain, three of the five resident dogs came to greet us and then promptly settled down to their naps at our feet under the table.

After our late lunch the rain had stopped enough for us to go birding along the ridge, where we saw a wealth of new species including the great blue turaco and the black-and-white casqued hornbill — both big birds. Down on the main road we stopped to get some red colobus monkeys in our spotting scope and attracted quite a crowd of locals. We encouraged them to look at the monkeys in the scope and they were flabbergasted at the sight of these animals so “close” — they thought they could reach out and touch them!

Though the adults in Uganda tended to be wary and unsmiling, the children were especially friendly. Everywhere we went, particularly in the car, almost every child would shout “How are you?” or “Hello!” and wave with big smiles as we passed by, sometimes running out from their huts or gardens. I always waved back, and Dennis thought I ate up all the attention like a beauty queen in the Rose Bowl Parade waving to her adoring fans. It was a treat to be greeted so heartily, I must admit.

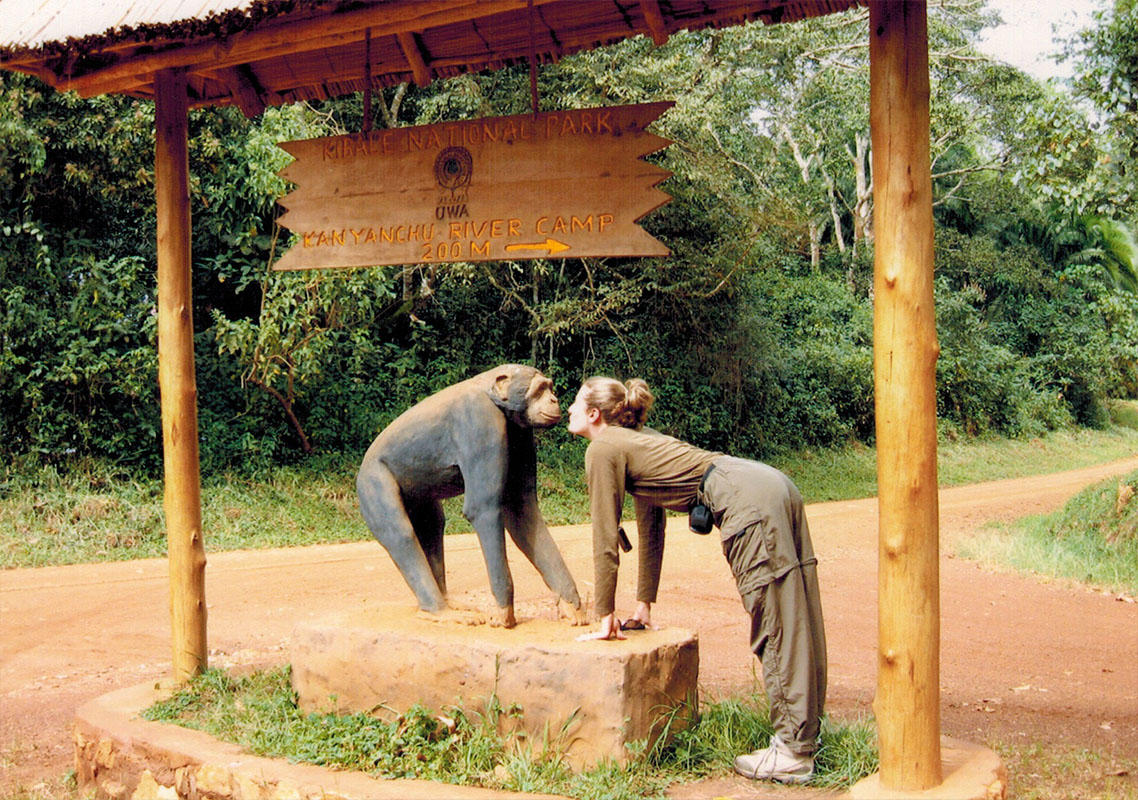

The next day we drove down through rolling hills of tea plantations into the forest of Kibale National Park, home of the chimpanzees. Before we reached the park the forest became very dense and we had to stop while locals cleared a large tree that had fallen across the road, blocking traffic. During our brief stop we spotted some more red colobus monkeys and another primate species — the gray-cheeked mangabey – crashing through the trees. More than 1,400 chimps live in Kibale National Park and some of them have been studied so widely that they have become habituated to humans, thus allowing visits by small groups of tourists.

The chimp community we saw on our forest walk had 14 members, including some mothers with infants and a few very large males. Two of them came hooting loudly and charging through the undergrowth, dashing past us very near and then scrambling up into the trees to join the others we had found just a few minutes before. We spent about an hour watching them but they were so high up and in the shade of the canopy that we could not get good photos. It astounded me that the other three people on our walk did not carry binoculars; it was impossible to get good views of the animals without them. We came across that time and time again — tourists in Uganda without binoculars. It is unthinkable to me to travel to see wildlife with only the naked eye — you simply cannot appreciate the animals and birds from a distance without optical help.

We spent our afternoon in the nearby Bigodi Swamp for a birdwalk, adding almost 20 new species to our life list. Part of the swamp has been set up with a boardwalk over the muddier sections through papyrus stands, but we found the best birding along a trail at the forest edge with a cornfield on the other. On our way back to the lodge we had to stop for a troop of baboons in the road, picking at one another’s coats (and other, more intimate places on their bodies) and catching bugs on the ground to eat. We spied one amorous couple right in the middle of making new baboons, and they stopped their action to give us the evil eye for the rude coitus interruptus. Eventually we moved on, getting back to our lodge once again near nightfall.

That was almost always the case — spending 12 hours a day in the field, either on foot or in the car. Being on safari was exhausting work. Our minds were constantly on alert as we scanned the landscape for any difference in color, shape, silhouette or movement that would hint at the presence of birds or wildlife. Every night we fell asleep within minutes or even seconds, drained by the day’s activities.